Stroudwater History

The Tate House Museum

The Tate House Museum, at 1270 Westbrook Street, is a National Historic Landmark. Being one of the oldest houses in Portland, it was built in 1755 for George Tate, his wife Mary, and their family. George Tate was a former British Royal Navy captain who was sent by a contractor to the Navy to oversee the felling of Great Eastern White Pine Trees (Pinus strobus) for use as masts and their shipment from the mouth of the Fore River in Stroudwater Village and on to England. This stately pre-Revolutionary house and museum, with its unique clerestory-gambrel roofline, is open to the public. For more info, go to: www.tatehouse.org

Great Britain had depleted its forests by the 17th century and looked to the tall, straight White Pines of Maine and New Hampshire to supply its appetite for timber for wooden ships, especially the old-growth pines for masts. White pine was a perfect solution to the Navy's problem. The trees were as tall as 150 feet, 5 feet in diameter and could weigh 10 tons. The wood was strong, flexible and light weight. White pine made the best and largest masts in the world.

King George’s Broad Arrow Mark

Photo Courtesy of William Cullina

King George's broad arrow, a vertical line topped with an upside-down "V," was slashed with a hatchet onto the bark of the straightest and tallest white pines which warned others away. To protect the marked trees, the King’s government appointed surveyor-generals for large tracts of land. Working in tandem with the surveyors, sometimes with a conflicting agenda, were the mast agents, who represented the interests of British firms that were contracted to provide masts to the crown. Captain George Tate, as a Royal Mast Agent, figured prominently in the local economy and colonial society of Falmouth on Casco Bay (as Portland was known until 1786).

Masts of the British Royal Navy

Supplied from Stroudwater Village

throughout the 18th Century.

Great Eastern White Pine (pinus strobus)

Stroudwater Burying Ground

The Burying Ground dates from 1727 and is registered with the National Registrar of Historic Places. The earliest recognizable stone dates from 1739.

“There sleep some of the men who felled the great mast pines growing in the early settlement of 1727, men who shaped bricks by hand, built the first homes, bridges, wharves, and mills. There sleep, too, the wives of the men-one and two and three and four—for those were the days when women died in childbirth and men remarried quickly in order that their children might be cared for and their hearths kept warm. The hallowed ground holds those that saw the village rise from a wilderness to the largest mast port in North America.”

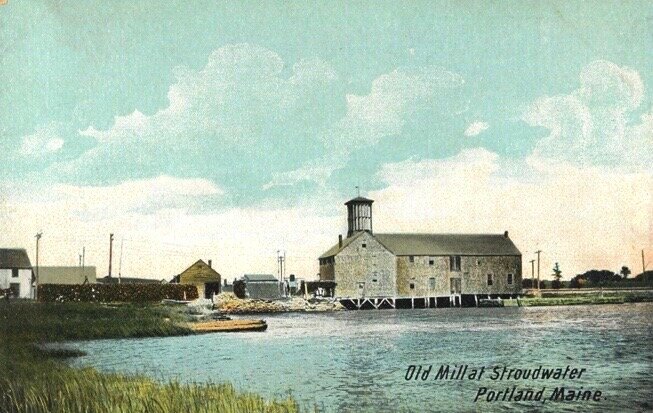

The Stroudwater River Dam

The current dam was built in 1850 and had been the site of many different mills, including this grist mill.

The Stroudwater River was used throughout the 19th century for moving logs down river and ice harvesting. Today the dam remains one of Portland’s iconic landmarks.

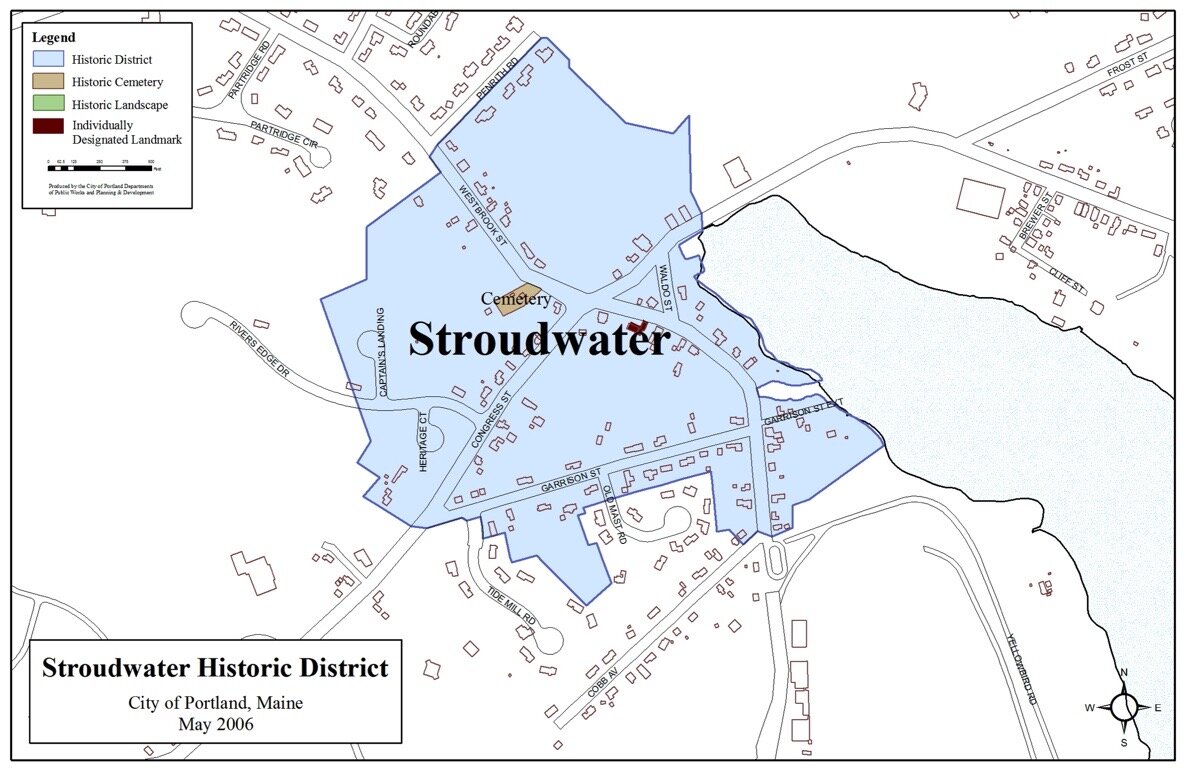

Stroudwater Village National Historic District

The National Registrar of Historic Places (N.R.H.P.) recognized Stroudwater Village as a National Historic District in 1973. Several of the residences included within the district are outstanding examples of the architecture of their period. The George Tate House has received recognition as a National Historic Landmark. The Thomas Means House, the Francis Waldo House, the Samuel Fickett house, the Martin Hawes house and the Dr. Jeremiah Barker house are of an equally exceptional quality. The other homes, still occupied, and built by less wealthy owners, never the less are of a high architectural caliber.

This 1865 map details historic structures and homes, many of which are still standing and lived in today.

The Tate House, the Burying Ground, as well as the entire Village District, are all registered with the N.R.H.P.

The Cumberland & Oxford Canal (1830-1872)

The Cumberland and Oxford Canal was a navigable waterway that extended from Harrison, Maine, on Long Lake, to Portland, Maine in the harbor. It operated from 1830 to 1870 and was used to transport timbers and other goods from the interior of the state to Portland. (see 1865 Map above)

The canal was opened in 1832 to connect the largest lakes of southern Maine with the seaport of Portland. The canal followed the Presumpscot River from Sebago Lake through the towns of Standish, Windham, Gorham, and Westbrook. The Canal diverged from the river at Westbrook to reach the navigable Fore River estuary and Portland Harbor. The canal required 27 locks to reach Sebago Lake at an elevation of 267 feet (81 m) above sea level. The canal had about 30 miles of natural water and 20 miles of man made sections.

In 1978, the local section for the American Society of Civil Engineers (ASCE) dedicated a plaque (above) to the canal. This plaque is located in a park dedicated to historic Stroudwater, on Congress Street/Route 9, at the intersection with Waldo Street.

Today, in Stroudwater, one can access the canal and walk along the original tow path where horses and mules once towed the canal’s long, flat bottomed boats hauling goods to Portland harbor.. The tow path is now part of the Fore River Sanctuary and Portland Trails which begins at Congress St. in Stroudwater and crosses the trail bridge (below) and continues for half a mile along the salt marsh.

The Fore River Portland Trails bridge in Stroudwater.